Considered one of the key figures of the new Asian postcolonial art, the painter of Philippine origin Manuel Ocampo has been proclaimed as one of the enfants terribles of the current art scene.

Throughout his career, Ocampo has given birth to a creative corpus to which it is impossible to feel a hint of indifference. Under a neo-expressionist language, Ocampo destroys any pictorial imposture or conventionalism with the aim of questioning and questioning the foundations on which our social and cultural identity has been historically built.

Fusing styles and multiple iconographic references, both religious and profane, Ocampo builds a visual narrative where the subversive, burlesque and satirical character of the images is elevated to the maximum power thanks to a caricatured and unbridled staging that oscillates between the scatological and the abject. Thus, the artist’s plastic universe, composed of already iconic elements such as crucifixes, penises, swastikas, money, knives, worms, cartoons and excrement, stand as emblems of his irreverent and absolutely critical attitude towards imperialist thought, discrediting to the point of annihilation the paradigm of the Eurocentric canon.

The iconoclasm of his creations attests to the magnitude of registers that his work reaches, where Ocampo immerses us to end up engulfing us in the maelstrom of multiple and disturbing references that question the violence, sex, religion and politics that are hidden behind his pictorial mannerisms.

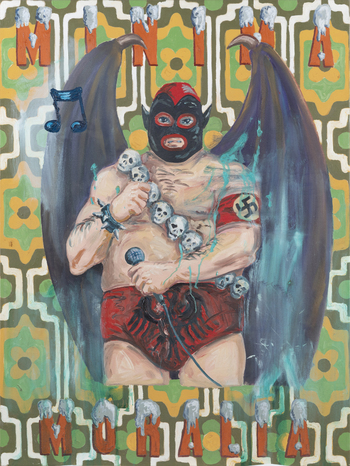

In this sense, the work in question (“El motivo compensatorio en la economía libidinal de la mala conciencia de un pintor”), belonging to an early stage in his career, evidences the coherence with which Ocampo has structured his work, and we can already detect in it the plastic character that will define his artistic career.

Behind a Mexican wrestling mask, with swastikas on his bare arm and Luciferian wings, this pop singer with a necklace of skulls gathers on his body a compendium of symbols that Ocampo empties of meaning to create a delirious mixture that short-circuits any simple interpretation. “Minima Moralia”, the title that accompanies the figure, refers to Theodor Adorno’s essay, a courageous book in which the author analyzed what capitalism inherited from Nazism. As the French philosopher did, the Philippine painter shreds through the field of painting the hoaxes of capitalist imperialism. With an aesthetic halfway between expressionism and pop, Ocampo intermingles the references of Mexican popular culture with the iconography of political propaganda with which he became known in the art world. In fact, the “grunge” frankness in talking about the moral dilemmas of modern society that characterized this stage, gave him a remarkable critical prestige that placed him at the top of the international contemporary map.

His work is undoubtedly the most accurate proof of the rebellious character of this “outsider” of the art scene, and of his firm belief that the world and our existence are completely dominated by chaos and absurdity.