The Evolution of Art: From the Orientalist Tradition to the Modern Vanguards

The set of pieces from the private collection to be auctioned on June 25 is one of those that allow us to trace a journey through the transformations that marked the evolution of art from the late nineteenth century to the middle of the last century. Undoubtedly, the intense production of this singular period gave birth to a progressive rupture with academicist conventions in order to embark on the path towards the creative freedom proclaimed by modernity.

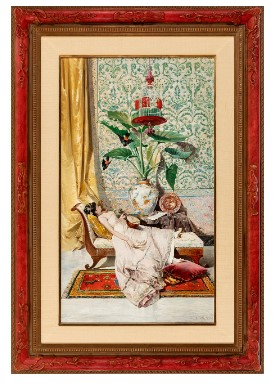

In this sense, we can begin the journey by situating ourselves in the European colonial expansion in North Africa, which during the 19th century was a determining factor in the desire of many artists to travel and explore an unknown world. The representation of its landscapes, customs and conflicts gave rise to the so-called orientalist painting, a genre with its own personality within nineteenth-century art. The artists, attracted by the exotic and distant, represented the oriental world under a prism dominated by the fantasy and evocative character that characterized the multiple stories about the lands of Mediterranean Africa and the Near East. The orientalist trend that was so much in vogue in the mid-nineteenth century is evident in works such as that of Margaret Murray Cookesley.

In the second half of the 19th century and within the period generically considered as realism, an artistic genre known as preciosismo proliferated, characterized socially by bourgeois taste and thematically by costumbrismo. The profuse detail and meticulousness that gives light to this type of scenes is reflected in works such as that of Baldomero Galofre, who during his stay in Rome was irremediably influenced by the aesthetics of Mariano Fortuny.

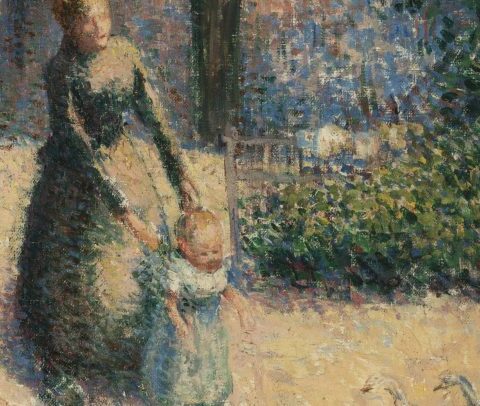

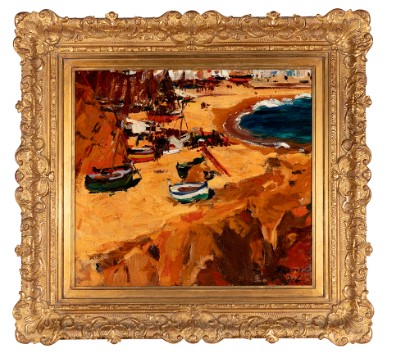

Between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, we moved towards a painting dominated by the stain and the loose brushstroke of artists such as Joaquim Mir who modernized the landscape genre in Spain. The deep imprint that the impressionists left on him is evident in the pair of landscapes in tender in which the artist reduces them to their basic elements through an excellent handling of light and color, which made him one of the greatest representatives of Spanish post-impressionism.

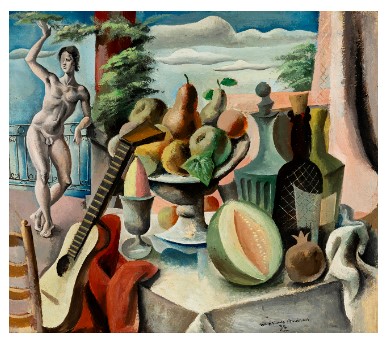

Another of the aesthetic trends that marked the art of this period, such as Noucentisme, can be seen in the work of Mariano Andreu, whose aesthetics are clothed in a modern classicism of a Mediterranean nature, related to the return to order that artists such as his admired Pablo Picasso captained.

As we entered the twentieth century, the emergence of the avant-garde movements completely revolutionized the art scene. As the world capital of art, Paris was an undeniable attraction for a multitude of artists of all nationalities who came to the French capital in search of new stimuli. Among them, it is worth mentioning the large number of Spanish artists who, like Miró, arrived in Paris fleeing from the artistic practices of a fin-de-siècle society anchored in the past. The multiple artistic movements and trends that followed one another and overlapped at a frenetic pace made Paris fertile ground in which to experiment and develop his creative personality.

In fact, we can relate Miró to another of the protagonists of the auction, the French artist and theorist Albert Gleizes, who shared several aesthetic and philosophical affinities with the Catalan master. In this sense, we have evidence of the cubist influence that Gleizes exerted on Miró, both through the exhibition held at Can Dalmau, as well as the famous book Du Cubisme (1911), which Miró treasured in his library throughout his life.

Already in the decade of the 20’s and 30’s the second migratory wave of Spanish artists settled in Paris, among which stand out figures of the stature of Hernando Viñes, Gomez de la Serna, Oscar Domínguez, Francisco Bores or Manuel Angeles Ortiz, who formed the so-called Spanish School of Paris. Far from being an artistically homogeneous group, this school is the result of a sum of personalities and artistic trajectories whose common denominator is to be found in the research, experimentation and assimilation of the multiple and novel artistic contexts that the historical avant-gardes offered them.

The exceptional community of artists that the city welcomed undoubtedly contributed to the creation of an atmosphere of intense creativity that made this artistic period a practically unrepeatable milestone.